Ziyin (Aurora) Lin, The University of California – Santa Barbara

Abstract

This paper investigates the divergent outcomes of the Assad regime during two critical phases of Syria’s recent history: its survival of the civil war from 2011 to 2021 and its collapse in 2024. While Assad initially endured a near-total territorial loss and widespread international condemnation, his regime ultimately regained control over much of Syria, aided by a fragmented opposition, robust support from Russia and Iran, and the international focus on defeating ISIL. However, in 2024, a dramatic reversal occurred: Assad was overthrown by a newly unified opposition amid shifting regional alliances, diminished foreign backing, and the erosion of his domestic and international legitimacy. Through a comparative analysis of military dynamics and foreign involvement, this paper explains how the very factors that once sustained Assad later contributed to his downfall.

Keywords: Syrian Civil War, Authoritarianism, Foreign Intervention, Regime Change, Middle East

- Introduction

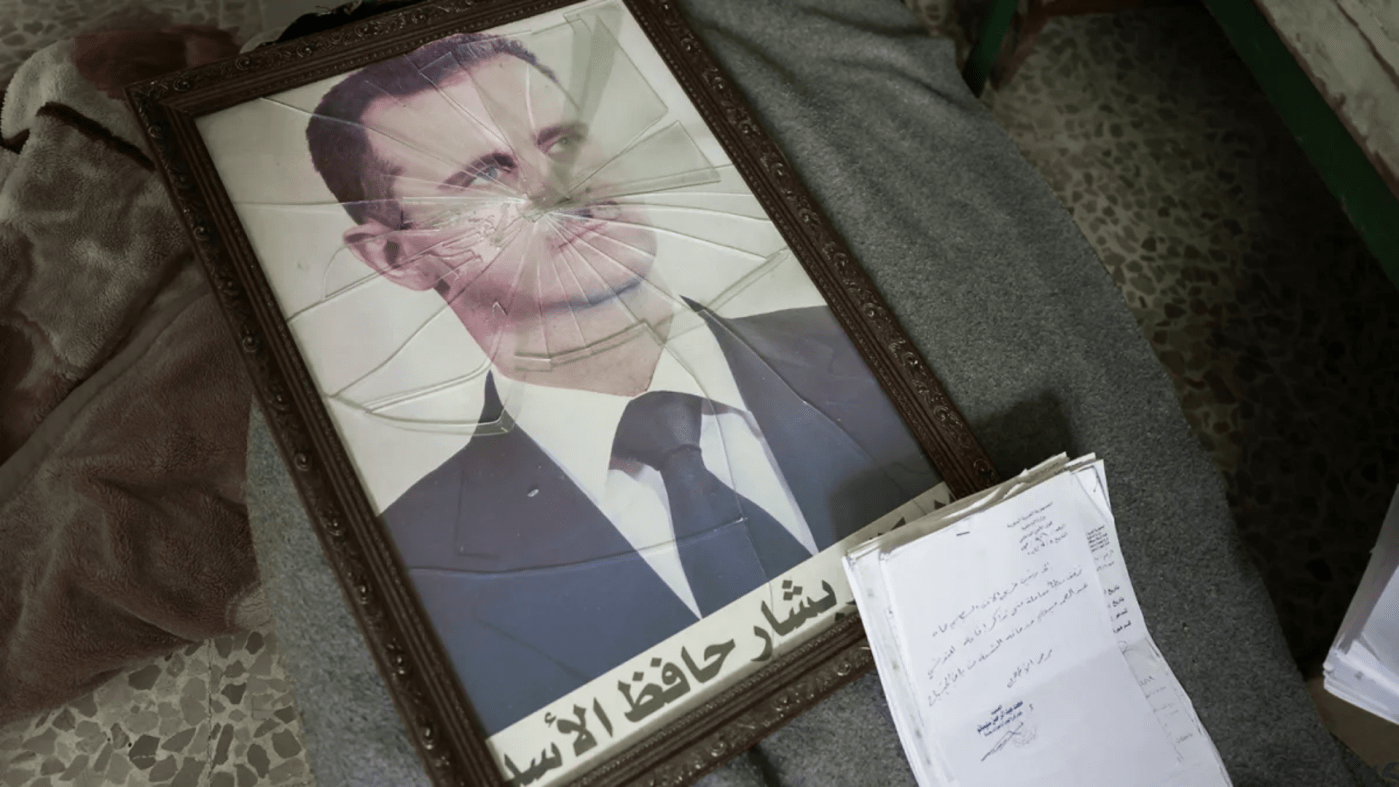

In March 2011, the brutal suppression of anti-government protesters triggered a devastating civil war in Syria, spiraling rapidly into a multifaceted conflict that would fuel global terrorism and one of history’s largest refugee crises. Initially, despite losing nearly 80% of Syrian territory to opposition forces, including the Islamic State (ISIL), the Assad regime managed a remarkable recovery, reclaiming all six major cities taken by the opposition and two-thirds of the country by 2021. Assad’s survival during these turbulent years was not solely due to regime strength. It was facilitated significantly by opposition fragmentation, steadfast Russian and Iranian backing, and the international community’s prioritization of combating ISIL. Yet, the regime’s apparent resilience proved fragile. On December 8, 2024, the Assad regime’s nearly 60-year-long Baathist rule in Syria came to an end after a swift, 12-day military offensive. This paper, therefore, seeks to explain the contrasting outcomes of these two critical moments in Syria’s recent history, addressing the central question: Why did Assad successfully survive Syria’s initial civil war from 2011 to 2021, yet fail dramatically in 2024? By comparatively examining key factors— military opposition dynamics and foreign geopolitical alliances—this paper argues that Assad initially survived Syria’s civil war (2011–2021) due to fragmented opposition forces, significant foreign support, particularly from Russia, and the US-led global priority to defeat ISIS, which legitimized his regime internationally. However, by 2024, these factors reversed: a unified opposition, reduced foreign patronage, and regional geopolitical realignments culminated in his regime’s swift collapse.

- Military Opposition: Fragmented Rebels vs. Unified Offensive

- 2011-2021: Fragmented Rebels

The Rebel Forces, which had been inspired by the Arab Spring movement and first started the anti-Assad campaign, failed to pose an effective challenge to the regime as it was internally divided and scattered. This disunity of the Opposition has been due to its own complicated and chaotic composition and the Assad government’s deliberate strategies.

- Complicated Composition

The armed units that comprised the Opposition forces were initially territorially scattered and lacking unified leadership. The main military force of the Opposition named itself as the Syrian Free Army (SFA), which has been broadly used by militias and defecting pre-government officers as a camouflage for their expansion and empowerment. Furthermore, as the forces that claimed to be affiliated with the FSA scattered across the nation and by mid-2013 incorporated 80,000 fighters, less than a third of the battalions were under the actual control of the Opposition’s Supreme Military Council (SMC). Although seemingly the Rebel Forces had a sudden horizontal presence across the whole country, the effectiveness of such a “highly decentralized and loosely coordinated network” is questionable. Because of the absence of central command and solidarity, one of the most disastrous results for the Opposition was that they were unable to transform from a nationwide guerrilla campaign to a coordinated field force that could threaten the government forces.

The Rebel Forces also failed to establish their legitimacy among the Syrian people. Although the Syrian Coalition (SC)—opposition leadership outside Syria—has repeatedly stressed their blueprint of a “civil democratic Syria,” the political authority of the Rebel Forces was gradually held in the hands of the leaders of some extreme battalions who expressed no wish to establish democracy. This realistic disparity has left a large portion of minorities in Syria with an unpersuaded mind to abandon the Assad regime and support the Opposition.

Besides the lack of leadership and failed establishment of authority, the Opposition is also inherently religiously conflicted. “These fighters have pitted moderate battalions loyal to the SMC against their Salafist counterparts, Syrians against foreign fighters, and, most recently, Arab Salafists against Kurdish forces in Syria’s ‘liberated ’ northeastern regions.” This description of the internal conflicts of the FSA has most directly illustrated the chaotic and divided nature of the Opposition. More importantly, a large portion of these clashes were ideology-oriented, suggesting a sectarian struggle in which a political settlement is nearly impossible. One of the most violent conflicts is between the Salafist militia and Kurdish troops, where the Kurds demanded to “preserve their independence from the SC”, marking a de facto disunity and division of the Opposition’s command.

- Assad’s Governmental Strategies

Apart from the divided nature of the Rebel Forces on their own, the Assad Regime has strategically leveraged this situation and accelerated its division through the demonizing of the protestors via both military operations and cultural propaganda.

The regime resorted to violence when the peaceful protests first began in 2011 and lasted until 2012. This action could be interpreted as a strategy to suppress the campaign as effectively as possible, while also being a tactic to delegitimize the Opposition. As the secular and peaceful marchers were cracked down upon, the Opposition had no choice but to use force, making themselves the root of social disturbance. Furthermore, the government deliberately created instability in the regions controlled by the Rebels through the exploitation of their air monopoly: Assad ordered airstrikes that drove millions of Syrians residing in opposition-held areas out of their homes and hindered the reconstruction and stability of these regions, significantly undermining the popularity of the Opposition.

Aside from these military operations, the Assad Regime also used cultural propaganda to demonize the rebels. The official media of the state continuously campaigned against the Opposition by associating them with Islamist extremists to “reinforce the uprising-as-Sunni-terrorism narrative,” which serves as a foil to the government’s public image as a secular regime and protector of the minorities. Through these social campaigns, the government presented the civilians with two obvious choices: a legitimate, politically correct regime or the brutal jihadists. Till this point, through both military operations and cultural propaganda, the Assad Regime has successfully exploited the initially divided nature of the Opposition and framed the Rebels’ reputation as a violent uprising force that 1) is incapable of maintaining regional instability and citizen security and 2) has extremist inclinations that may seriously undermine national foundation and international image. This creation of the notion of a “common enemy” in turn sustained the defensive solidarity of the Syrian people and the regime, most remarkably shown by the alliances of the Alawites and other minorities.

Nevertheless, some may argue that Assad’s regime initially intended a violent transformation of an original peaceful protest that merely demanded social reforms, to a sectarian armed organization, which is of no benefit to itself, as the regime has dragged the nation into a bloody civil war. Evidence has shown that “the regime has failed to defeat the insurgency” that it provoked, as it was continuously defeated in the south and near its capital. However, this argument could be rebutted as a thorough constitutional and economic reform directly contradicts the dictatorial nature of Assad’s regime and will seriously threaten the sustainability of his presidency. A crippled control over his government serves as a much harder target than extremism and fragmentation that could be addressed directly with accountable military confrontation.

Another perspective is that the sectarian cleansing of minorities in Syria’s suburban areas was a result of drastic demographic changes during the civil war, largely orchestrated by the Assad regime, which in turn undermined the regime’s claim of being a secular government that protects minorities. Furthermore, the local minorities have long submitted their allegiance to Damascus out of fear rather than a sense of cultural belonging and solidarity. However, this argument could also be proven to be invalid, as although the public image of the Assad Regime before the war was secular, the regime has shown remarkable capability to adapt to the mass politics and the political situation. The significant increase in the number of Alawite senior officers and administrators in Assad’s government from the outbreak of the protest to the later years of the civil war reflects the regime’s evolving policy of the regime to align with the war’s sectarian dynamics—a process it initially facilitated, was later influenced by, and ultimately intensified through this cyclical interaction.

This “interaction effect” between the government’s strategy and the Opposition’s internal evolution eventually led to a stalemate between the two sides in 2013. While no actual progress has been made, a large portion of the lands was occupied by the poorly managed Opposition, which not only created power vacuums that allowed terrorist groups to send in foreign fighters but also brought in international interventions that later proved beneficial for the survival of the Assad regime.

- 2024: Unified Offensive

In stark contrast to the fragmented opposition during the 2011–2021 civil war, the 2024 conflict witnessed an unprecedented unification of rebel forces. Organizational unification, expanded coalition strength, and external abandonment converged to dismantle the structural foundations of Assad’s regime in a matter of weeks.

A coalition comprising Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), and the U.S.-supported SFA coalesced under a centralized command structure. This alliance was orchestrated by Ahmed al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani, who had previously led HTS. The offensive commenced on November 27, 2024, with a surprise attack on Aleppo. Within days, rebel forces captured key cities, Aleppo fell by November 30, Hama by December 5, and Homs by December 7. These rapid successes effectively severed Damascus from the Alawite coastal regions, undermining the regime’s strategic depth. Simultaneously, in southern Syria, the Southern Operations Room—a coalition of former rebel factions—launched an assault on Daraa Governorate. By December 7, they had advanced into the southern suburbs of Damascus. The convergence of northern and southern rebel forces culminated in the capture of Damascus on December 8, marking the end of Assad’s rule.

Several interrelated factors contributed to the swift and decisive collapse of the Assad regime in 2024. First, the establishment of a unified command structure under the leadership of Ahmed al-Sharaa marked a critical turning point in the organizational capacity of the opposition. Unlike the fragmented and often competing factions of the earlier civil war period, the newly formed coalition was able to coordinate military operations across multiple fronts with strategic precision. This centralized leadership allowed for synchronized offensives, efficient resource allocation, and consistent messaging, which in turn bolstered morale and operational momentum among rebel forces.

Second, the strategic integration of diverse factions, including some groups that had previously reconciled with the regime, significantly expanded the rebels’ manpower, logistical capabilities, and territorial access. This broad-based coalition combined the strengths of ideologically varied units, ranging from Islamist to nationalist, to form a pragmatic military alliance with shared objectives. The consolidation of these groups not only increased battlefield effectiveness but also gave the opposition greater legitimacy in the eyes of both local populations and foreign backers.

Third, the rebels skillfully exploited the mounting vulnerabilities of the Assad regime. By 2024, Assad’s forces were overstretched, under-resourced, and suffering from low morale, a situation exacerbated by the substantial reduction in support from traditional allies such as Russia and Iran. Both countries, preoccupied with their strategic challenges—Russia with its deepening military quagmire in Ukraine, and Iran with intensifying Israeli airstrikes and internal instability—scaled back their material and advisory assistance to the Syrian regime. This decline in external patronage critically weakened Assad’s ability to sustain multi-front defenses, leaving key urban and strategic areas exposed to coordinated rebel advances.

This cohesive and strategically adept opposition force overwhelmed the Assad regime, which had previously relied on exploiting divisions among rebel groups. The 2024 offensive demonstrated that unified military opposition, coupled with strategic planning and the exploitation of regime vulnerabilities, could decisively alter the balance of power in Syria.

- Foreign Support & Geopolitics: Lifeline vs. Abandonment

During the initial Syrian civil war, Assad received robust foreign patronage, notably from Russia and Iran, which provided him with critical military, economic, and diplomatic support, significantly outweighing the fragmented international backing received by opposition forces. This substantial external assistance insulated Assad from international condemnation and bolstered his military capabilities, ultimately enabling his regime to survive and regain control despite severe domestic challenges. In a dramatic reversal in 2024, Assad’s external support sharply deteriorated just as the opposition forces unified under enhanced foreign patronage, reshaping regional geopolitics. This newfound opposition backing from Turkey, Gulf States, and indirectly from Western nations decisively undermined Assad’s geopolitical position, culminating in his regime’s swift and comprehensive collapse.

- 2011-2021: Strategic Alliances and International Shield

- US-led coalition against ISIS

The consequential emergence of ISIL shifted the focus of war and the primary aim of the international community, which not only eased the western pressure over the Assad regime through their demand for its removal, but has also significantly aided in the defeat of the most prominent enemy of the regime – ISIL. ISIL began its expansion in 2013, as on March 4th, the city of Raqqa was captured by opposition, the city in which also resided a vast amount of Al-Qaeda and ISIL fighters. At its peak, the Islamic State occupied about a third of Syria, with the government only less than 1/5 of its territory, posing an imminent threat to the survival of the regime, which, with continuous defeats, has lost initiative and become strategically passive. The abrupt uprising of such an impactful and ruthless terrorist group has quickly captured the attention of the international community. September of 2014 marked a monumental shift in the war and the strategy of the Western world. In terms of direct foreign intervention, on September 10th, the United States officially announced its participation in a direct military operation in the region, with the formation of a broad international coalition to defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). President Obama, in his speech, announced four operation guidelines: enforcing a systemic campaign of airstrikes, sending additional 475 service members to Iraq to support Iraqi and Kurdish forces with training, drawing on the US’ counter-terrorism capabilities and providing humanitarian assistance, signifying an entirely different strategy in contrast to the previous non-intervention policy.

Following this establishment of the US-led Coalition in late 2014, in 2015 the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) issued several vital Resolutions in November and December, in which this international body with the highest executive power, “calls upon Member States that can fo do to take all necessary measures,…on the territory under the control of ISIL” and to “intensify their efforts to stem the flow of foreign terrorist fighters to Iraq and Syria.” UNSC has also authorized international sanctions against ISIS and affiliated personnel: “Asset Freeze”, “Travel Ban”, and “Arms Embargo”, symbolizing an official new global aim of combating ISIS in the Syrian Civil War.

Apart from foreign intervention measures that greatly assisted the survival of the government troops under the offensive expansion of ISIS, the world has also witnessed a remarkable shift in Western political attitudes towards the existence of the Assad regime itself. The U.S. changed its tune as at a meeting in January 2015, the U.S. secretary of state John Kerry “omitted any reference to regime change in Damascus, voluntarily or involuntarily.” President Obama has also rejected the possibility of the U.S. intervening directly to remove Assad. Hence, the emergence of ISIS has shifted the international community’s priority completely, with the US’s “Islamic State First” Strategy, not only would Assad be militarily assisted to defeat ISIS, the effect of which would be discussed below, but also has retained its political legitimacy.

As a result of the powerful US-led coalition airstrikes, which includes troops from the United Kingdom, France, and several European allies, and MENA regional powers such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia, with the assisted ground offensives launched by the Syrian Democratic Forces led by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, Nusra Front and also Assad’s government troops, “ISIS’ advance has been in the doldrums and it is now in a defensive mode” and “the expansion of the group seems very difficult for now.” These are statements concluded in a report published in August of 2015, merely a year after the establishment of the US-led coalition, indicating its significant and effective role in defeating ISIS. Aside from the blockade formed by the US-led offensives, a decline in the sources of fighters also results in the stalling of ISIS’s advances, which is an achievement credited to the previously mentioned international community’s effort to halt the influx of such fighting force. Moreover, the turning point of ISIS’ shift “from assault to defense” was their failed attack on the Kurdish City of Kobane, which is a result of the US-led airstrikes.

Consequently of the international community’s effort, in six months ISIS had already lost 9.4% of its occupied land, marking a decrease of 60% by mid-2017, followed by an 80% down in its revenue. Apart from the territorial advantage gained by the Assad regime from the defeat of ISIS, its legitimacy has been reassured on an international level, as Russia and the U.S. have reconciled over the general aim in the Syria crisis, although “Syria’s main opposition and their Turkish and Saudi backers will not like it,” this “big power consensus” is likely to “enable Assad to survive.”

Nevertheless, some analysts have suggested that the emergence of ISIS was not the reason behind the different Western political attitude towards the Assad regime. Rather, it was the entrenchment of the government that has shown in the stalemate with the Opposition, its evolving adaptation to this civil war (e.g. intensified patrimonial Alawite administration), and the regime’s determination to survive given Assad’s successful re-election in 2014 despite the ongoing Civil War, that has already gradually convinced the western bloc, though reluctantly, that a complete removal of the present regime was unfeasible. Nevertheless, although such a fact has been “uncomfortably clear”, the U.S. and its European allies continued to adopt a hedging strategy until the outburst of ISIS developed to an uncontrollable extent in 2014, when on August 7th, the U.S. launched its first airstrike in Syria. A more convincing counter-argument is that not all territories regained from ISIS through this international military assistance fell under the regime’s control, hence the argument that such a shift in the focus of war did not contribute to the survival of the Assad regime. Although ISIS’ territory was reduced by 9.4%, the Syrian Government’s occupied land experienced an even larger loss of 16%, while all the gains belonged to Iraqi forces, the Kurdish forces, and the Sunni rebels. However, it should be noted that this data was analyzed in an early stage of foreign intervention, as the government was still suffering from the offensives of ISIS and most notably, before the intervention of Russia, a steady ally of the Syrian government, who would ensure the re-captured land fell under the control of the government troops.

Although the US-led coalition contributed greatly to the defeat of ISIS, it is critical to point out that they did not participate in restoring Assad’s rule; rather, it was mainly for the elimination of international terrorism, from which the Assad regime benefited, as they shared the same enemy. The Kurdish forces and Opposition forces, on the other hand, have long been the west’s ally in the Syrian Civil War, and they closely cooperated in terms of land and air operations, hence the territorial gains of these two forces are logical in this early phase of international intervention, the situation of which would be changed as soon as Russia joined in the war in September, 2015.

- Russia’s Military Intervention and Diplomatic Efforts

Russia’s military intervention and diplomatic efforts eventually secured Assad’s survival in the Syrian Civil War. The aims of Russia in the Civil War can be complicated, as although its official goal was to “fight against internationally recognized terrorist groups, Daesh and al-Nusra,” it also combated opposition battalions in operations, which implicated its affirmed alliance with the Syrian government in re-seizing control of the nation.

Russia has deployed more than 40 warplanes, navy ships and submarines, strategic bombers, and at its peak, 5000 personnel in Syria. Apart from direct military operations, this powerful ally also recruited Russian mercenary military companies to guard territories with oil and gas fields to secure financial revenue for the Syrian government. It has been reported by a Syrian local news agency that the ISIS oil trade and supply routes in the Syrian Desert have been heavily struck by Russian airstrikes. By March 2016, before the withdrawal of the Russian troops from Syria, they had assisted the Syrian government in reclaiming 10,000 square kilometers of territory. In contrast to the 1/6 of territory controlled by the government, by spring 2018, Assad’s regime captured more than 57% of its nation with the occupation of principal rebel strongholds – Eastern Aleppo and Eastern Ghoutachoose – and that “Anti-Assad rebels and radical Islam groups in Idlib combined hold less than 11% of the territory,” marking the successful role of Russia military in assisting the government troops not only to combat ISIS but also to rebuild its national authority and control as opposed to all confronting forces.

Besides devoting full military efforts, on the international level, Russia served as a diplomatic shield to Syria. It has made numerous attempts in the UN to block the international sanctions and also any measures that may undermine the existence or imply the removal of the Assad Regime: it has vetoed twice in UNSC in 2011 and 2012, objecting condemnations towards the war atrocities in Syria, blaming the formation of a Contact Group for Syria, the ‘Group of Friends of Syria’, as a violation of international law. Before the uprising of ISIS, Russia has protected Syria in terms of its legitimacy on an international level, regardless of being isolated from all the other 13 member states in the UNSC (except from China), and hence the international community, combining its restless military aid as soon as Syria requested for support in September, 2015, has proved its destined goal to restore Assad’s rule and its triumph, as the Director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency stated, “Russian reinforcement has changed the calculus completely” and that Assad “is in a much stronger negotiating position than he was just six months ago.”

Nevertheless, a major challenge towards the effectiveness of Russia’s alliance is that although “Russia prevented the fall of Assad”, it “has not been able to restore the whole country to him,” as even a thorough military victory would result in a fragmented Syria, occupied by three forces: the government, the Kurdish Forces, and Turkey and its Islamic counterparts. To rebut this statement, attention must be drawn to the small amount of land occupied by the other two forces at present: 11%. Not only is the full conquest of its territory a matter of time, which might be prolonged, but the fact that Assad’s regime now gains initiative in the situation and that Russia now serves as a major influencer in this matter would secure Assad’s legitimacy and authority in a postwar settlement. Thus, despite several different perspectives, Russia’s military intervention and diplomatic efforts have successfully ensured the continuity of the Assad Regime’s existence.

- 2024

In 2024, the Assad regime confronted an unprecedented geopolitical reversal, dramatically shifting the external power dynamics that had previously underpinned its survival. Crucially, the regime’s longstanding reliance on steadfast allies—Russia and Iran—experienced severe disruption. Russia, a key military supporter whose intervention in 2015 had decisively bolstered Assad’s military capacities and enabled substantial territorial reconquests, found itself deeply embroiled in the protracted conflict in Ukraine. Facing extensive economic sanctions, global diplomatic isolation, and substantial losses on the Ukrainian fronts, Moscow significantly reduced its strategic engagement in Syria. Russia’s strategic calculus changed dramatically due to its overstretch in Ukraine, leading to a marked scaling back of its military and economic commitments in Syria, thus weakening Assad’s military capability and political leverage. This strategic disengagement not only diminished Assad’s defensive capabilities but also undercut the symbolic strength he had enjoyed through Russia’s international diplomatic protection and military assurances.

Simultaneously, Iran—historically Assad’s most consistent regional ally—faced its mounting crises. Israeli airstrikes intensified significantly in late 2023 and early 2024, systematically targeting Iranian-affiliated militias, weapons depots, and infrastructure within Syrian territory, notably in Damascus suburbs and southern Syria. Israel’s targeted campaign significantly weakened Iran’s strategic foothold in Syria, forcing Tehran into a cautious withdrawal of Revolutionary Guard advisors and affiliated militia groups. This scaling back of Iranian presence critically undermined Assad’s capacity to maintain territorial control, particularly in contested areas previously secured through Iranian proxies.

Amid these reductions in external support for Assad, a concurrent regional realignment unfolded, bolstering the opposition’s position substantially. Turkey emerged prominently, galvanizing and supporting the SNA while also facilitating closer cooperation with HTS. Turkey’s increased coordination with rebel factions through intelligence sharing, logistical support, and cross-border military supplies decisively altered the opposition’s battlefield effectiveness in 2024. The United States also subtly expanded its support through increased provision of intelligence and limited arms shipments to select opposition groups, notably the SFA, reflecting a geopolitical pivot towards regime transition as a pathway to regional stabilization. Moreover, Israel’s strategic bombardments, while aimed primarily at Iranian assets, further degraded Assad’s military infrastructure, indirectly assisting opposition advances.

This multifaceted geopolitical reconfiguration ultimately isolated Assad diplomatically and militarily. Gulf States, previously ambivalent or even tacitly accepting of Assad, shifted towards openly backing a transitional political solution led by the unified opposition coalition, driven by pragmatic considerations to weaken Iranian regional influence. The alignment of interests among Turkey, Gulf States, Israel, and implicitly the United States created a potent external framework favoring Assad’s removal, fundamentally reshaping regional geopolitics and eliminating Assad’s longstanding external lifelines. Thus, this rapid erosion of external support, combined with the strengthened cohesion and coordination among opposition forces, conclusively sealed the Assad regime’s strategic isolation and precipitated its dramatic collapse in December 2024.

- Conclusion

The contrasting outcomes of the Assad regime in Syria—its endurance through the civil war from 2011 to 2021 and its sudden collapse in 2024—underscore how deeply regime survival is contingent on both internal dynamics and shifting geopolitical landscapes. Assad’s initial resilience was not the result of overwhelming regime strength, but of a fragmented opposition, steadfast foreign backing from Russia, and a global security climate that prioritized defeating ISIL over demanding regime change. Through both strategic manipulation of sectarian narratives and calculated reliance on external military and diplomatic support, Assad navigated existential threats and reasserted partial control over Syrian territory.

However, the very conditions that enabled the regime’s survival later unraveled. By 2024, the Syrian opposition had achieved unprecedented unity, coordinating under centralized command and launching a highly effective nationwide offensive. At the same time, Assad’s core allies faced their geopolitical setbacks—Russia bogged down in Ukraine, and Iran weakened by Israeli airstrikes and internal constraints. Western and regional actors, once ambivalent, recalibrated their strategies, providing indirect but decisive support to the opposition coalition. With eroded legitimacy, depleted foreign support, and a unified rebel front confronting a hollowed-out military, Assad’s fall was not only plausible but inevitable.

Leave a comment