Sasha Allen, The University of California – Santa Barbara

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates how key international organizations — NATO, the UN, the WHO, and the WTO — have responded to recent shifts in U.S. foreign policy marked by nationalism, unilateralism, and disengagement from multilateral commitments. As the traditional guarantor of the post-World War II international order, the United States has played a central role in shaping and sustaining global institutions. However, under the Trump administration and its ‘America First’ doctrine, international organizations have faced increased pressure to function with reduced U.S. support. Drawing on realist and constructivist theories of international relations, this study analyzes the strategic, financial, and institutional adaptations employed by these organizations to maintain their relevance and effectiveness in an era of American retrenchment. It finds that while U.S. engagement remains vital, the capacity of international organizations to evolve through diversification of leadership, innovation, and coalition-building will be essential to sustaining global governance amid a shifting geopolitical landscape.

Keywords: International Organizations, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, United Nations, World Health Organization, World Trade Organization, Unilateralism, Multilateralism, International Security

Introduction

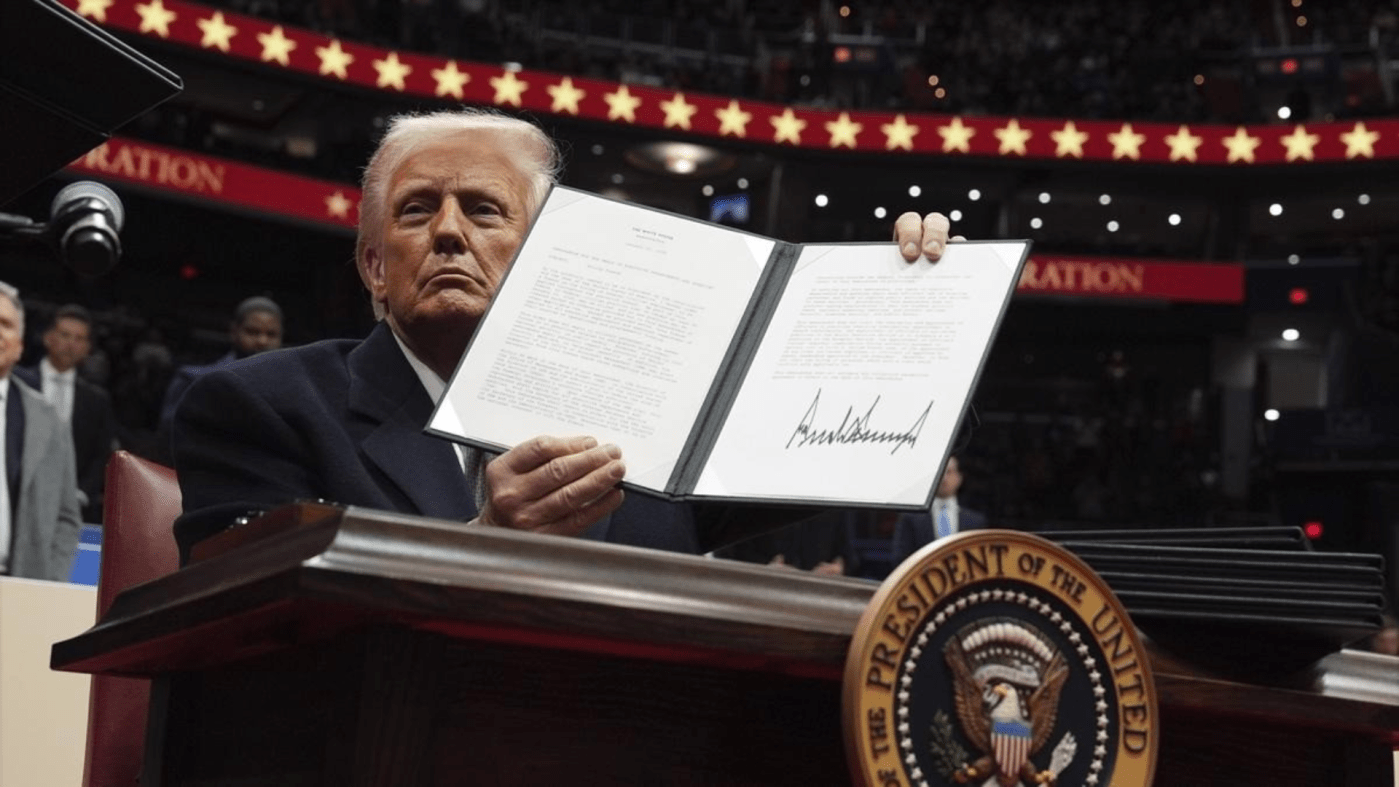

Since the end of the Cold War, the world has been undoubtedly unipolar, with the U.S. in the hegemonic position at the top. But changing dynamics and the rise of global competitors such as China and Russia are calling into question whether the U.S. will maintain its unique hegemonic position. The United States’ increasingly nationalist, protectionist, and isolationist policies could potentially be the downfall of international collaboration and stability in the international order. Shifts in American foreign policy have significant implications for the international system, particularly for institutions that have long depended on U.S. support to function effectively. International Organizations (IOs) play a crucial role in global governance, providing institutions for economic cooperation, security coordination, and diplomacy. In an anarchic world, their effectiveness often depends upon the commitment of superpowers, especially by the United States. Under Donald Trump’s presidency, with lingering effects from his first term and a renewed ‘America First’ agenda, the U.S. has increasingly prioritized unilateral actions over multilateral cooperation, challenging the effectiveness and stability of established IOs. Threats of funding cuts, critiques of efficiency, and withdrawal from past agreements have forced IOs to reconsider their strategies for survival and relevance with less U.S. involvement. Despite pressures from U.S. disengagement, IOs have demonstrated resilience through adaptation. By seeking alternative funding sources, forming new strategic alliances, and adjusting policies, maintaining influence in a changing political landscape became possible. This paper examines the impact of recent U.S. policy shifts on key international organizations and analyzes the survival strategies they have employed to navigate these challenges. The analysis will focus on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the United Nations (UN), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Trade Organization (WTO), as each plays a critical role in global security, diplomacy, public health, and economic cooperation — sectors directly shaped by changes in U.S. engagement and leadership. While U.S. foreign policy remains a defining factor of global governance, the ability of these institutions to adapt will shape the future of collaboration in an increasingly fragmented world.

Background

The terms International Organizations (IO), or International Institutions (II), have been used to define a wide collection of actors in the international system, although most often refers to formal institutions. Major political events have influenced the very existence of such organizations, as well as fields of study surrounding them. Following the Vietnam War and the U.S. ending the Gold Standard in 1971, it became clear to scholars that the earlier emphasis on formal structures and multilateral agreements had been overstated. These events highlighted the implications of relying solely on formal institutions and legal agreements to maintain the global order, as powerful states continued to act unilaterally when it suited their interests, undermining the effectiveness of multilateralism. Since these events, international governance has been studied more broadly, defined by Stephen Krasner (1983) as “rules, norms, principles, and procedures that focus expectations regarding international behavior.” Furthermore, John Mearsheimer (1994), the leading practitioner of the neorealist school, defines institutions as “sets of rules that stipulate the ways in which states should cooperate and compete with each other.” This study will hone into the latter definition.

International organizations often struggle to achieve their intended goals due to the dominance of political realism in the international system. Mearsheimer, in Anarchy & the Struggle for Power, argues that it is the structure of the international system itself rather than specific traits of countries that causes great powers to act aggressively and seek control at the expense of its neighbors. The anarchic nature of the international system compels states to maximize their power rather than settle for an equal power balance — and this desire does not simply disappear when states come together in an IO. Regardless of any apparent desire for states to mutually cooperate in the international system, balance of power politics will dominate and states will always act in favor of maximizing their own power and status. In IOs, this translates into a reluctance to fully commit to collective action or cede certain national interests in pursuit of common goals. Instead, member states selectively engage with international institutions, exploiting them when advantageous and disregarding them when they conflict with their national interests. The pursuit of consensus and cooperation becomes challenging, as divergent interests and power asymmetries undermine the effectiveness of collaborative international efforts. Realist tendencies contribute to a lack of trust between states, hampering genuine collaboration and impeding progress on critical global issues, such as peacekeeping and humanitarian intervention. As a result, international organizations consistently fail to exert meaningful influence or create lasting benefits in a world shaped by political realism.

The prevalence of realism in international relations poses significant challenges for the future of international cooperation. As states prioritize their own interests and power dynamics continue to shape global politics, skepticism and disillusionment with international organizations are likely to increase. However, a contrasting perspective of constructivism could offer hope for reshaping the future of international cooperation. Alexander Wendt’s argument challenges the deterministic nature of realism by contending that self-help and power politics are not inherent features of an anarchic system, but rather emergent from social processes and practices. According to Wendt, anarchy itself does not dictate state behavior; instead, it is the actions and interpretations of states that shape the system. Under this view, the norms, identities, and shared understandings among states play a crucial role in shaping their behavior and fostering cooperation. By emphasizing the potential for change through social construction and collective action, constructivism offers a more optimistic outlook for international cooperation. This perspective suggests that by altering the prevailing norms in fostering a culture of cooperation and mutual understanding, it is possible to mitigate the impact of realist tendencies, and build a more inclusive and effective system of global governance. Thus, while realism presents significant challenges to international cooperation, constructivism provides a promising alternative framework for envisioning a more cooperative and peaceful future in global affairs.

NATO & Military and Strategic Adaptation

NATO is the foremost example of an international organization forced to adapt to shifting U.S. foreign policy priorities, particularly under the two Trump administrations. Trump has frequently criticized NATO, questioning its value and accusing member states of relying too heavily on U.S. military support without meeting their own defense spending commitments. His rhetoric has raised concerns about American commitment to collective defense, a core pillar of the alliance outlined in Article 5 of the NATO charter. Article 5 states that “an attack on any member state is an attack on all.” Trump’s statement that he would “encourage Russia to do ‘whatever the hell they want’ to any NATO country that doesn’t pay more for its defense” has decimated cohesion within the alliance and raises doubts about deterrence credibility. In 2023, as Russia entered a second year of full-scale war on Ukraine, NATO members collectively vowed to spend at least 2% of GDP on national defense budgets. Now, the Trump administration is insisting that number be raised to 5%, an investment at unprecedented scale. However, it remains unclear how many European member states will be able to reach even a 3.5% investment. Notably, the U.S. at 3.19% in 2024 is the only ally whose spending has dropped after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Trump, nevertheless critical of so-called ‘freeloaders’, has proposed a series of changes to both the organization and terms of U.S. participation. He has proposed restructuring U.S. engagement with NATO to prioritize support for member states that meet the defense spending benchmark. This could include offering preferential military aid or strategic cooperation to compliant states, while potentially withholding assistance during crises or emergencies from those that fail to meet the spending threshold. Moreover, he has signaled to European allies that the U.S. will reduce its overall military presence across Europe and reposition its forces to more actively defend or station in countries that meet the NATO defense spending target. In response to these pressures, NATO has initiated a series of institutional adaptations that can be interpreted as both reactive and proactive survival strategies. One of the most visible adaptations was the acceleration of defense spending among member states. As of 2024, at least 23 of the 32 member states are expected to have achieved the 2% of GDP threshold for defense spending — up from just three in 2014 — largely in response to U.S. pressure. While the push for increased defense spending across the board predates the Trump era, his unpredictable intentions brought a new sense of urgency. Beyond financial adaptations, NATO has also begun expanding its strategic focus to maintain relevance amid internal uncertainty. In 2019, the alliance adopted new priorities centered on hybrid warfare, cyber defense, space operations, and strategic competition with China. These shifts reflect the understanding that NATO’s long-term survival requires more than traditional military readiness — it necessitated institutional agility and political cohesion in an era of evolving threats. For example, NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept emphasized resilience, innovation, and digital transformation — key areas where consensus could be built despite wider political divisions. Resilience refers to strengthening national and collective defense systems against both military threats and non-traditional challenges like cyberattacks and disinformation. Innovation involves investing in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, space capabilities, and autonomous systems to maintain a strategic edge. Digital transformation includes modernizing command structures, communication networks, and data-sharing systems. Facing a rapidly changing security landscape, NATO has been compelled to undergo what Colonel Mark C. Boone described as a “revolution in thinking.” The 21st century has ushered in a new era of technological warfare characterized by hypersonic weapons, autonomous systems, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and ubiquitous sensors. These developments are not only changing the tools of war but also challenging the ethical, operational, and institutional foundations of military strategy. Boone argues that to maintain strategic overmatch, NATO must foster a culture of decentralized decision-making, where trust, speed, and subordinative initiative are valued as essential elements to modern battlefield success. This cultural shift requires systemic reforms, from training and professional development to command structure and alliance-building. U.S. defense planning in the Indo-Pacific, particularly with long standing partners such as Australia, has already begun adopting the model of decentralized, tech-enabled coordination. This reflects Washington’s growing strategic prioritization of the Indo-Pacific region as it reduces its military footprint in Europe and urges NATO allies to carry more defense responsibilities. In response, NATO has taken steps to institutionalize similar flexibility within Europe. France and Britain have taken on expanded roles in coordinating Eastern European defense planning, and joint command headquarters in Brussels are being reorganized to distribute more decision-making power among European members. NATO has also moved to tighten operational links with countries such as Japan, Australia, and South Korea, in efforts to globalize the alliance’s strategic scope and reduce reliance on a politically volatile US. The future of NATO hinges on its willingness to adapt — by embracing innovation, sharing leadership, and reducing overreliance on the United States.

The UN & Financial and Leadership Diversification

The United Nations (UN), long a pillar of postwar multilateralism, had to confront serious internal reckoning in the wake of Trump-era foreign policy, which undermined both its financial stability and political legitimacy. The ‘America First’ doctrine undermined multilateral engagement, most notably through U.S. withdrawal from key UN-affiliated agreements and institutions including the Paris Climate Accord and the UN Human Rights Council. The U.S. is no longer willing to serve as the primary underwriter of global cooperation without transactional gains. Trump’s rhetoric routinely criticized the UN as “ineffective” and “anti-American”, calling for major funding cuts and threatening to withhold U.S. contributions unless reforms were made. As the UN’s largest single donor, contributing nearly $13 billion and over 25% of total funding, the threat of U.S. disengagement triggered immediate concern over financial stability and power balance within the institution. In response, the UN initiated a quiet but strategic effort to diversify its financial contributors and leadership base. Secretary-General António Guterres undertook a multi-pronged funding reform campaign beginning in 2019, which included lobbying member states to increase assessed and voluntary contributions and instituting a liquidity-saving policy that cut operational spending by 20%. China, Germany, and Japan stepped up their funding roles to fill the gaps left by reduced U.S. involvement. China, for instance, increased its share of the peacekeeping budget from 6.6% in 2016 to over 18% by 2024, while also expanding its influence in UN leadership positions across agencies like the Food and Agriculture Organization and the International Telecommunication Union. Clearly, the UN is recalibrating its internal power structure to reduce reliance on any single state and enhance resilience through a multipolar leadership framework. Additionally the UN is adapting diplomatically to the erosion of American multilateralism by empowering regional partnerships and creating new coalitions of middle powers. “The Alliance for Multilateralism”, co-founded by France and Germany in 2019, emerged as a forum for states committed to upholding international norms despite U.S. retrenchment. This alliance has since played a critical role in supporting the UN’s global health, climate, and human rights initiatives, effectively backstopping the organization during moments of U.S. withdrawal.

These adaptations illustrate a clear institutional strategy — rather than directly confronting Washington, the UN has moved to insulate itself by distributing leadership and forming strategic partnerships. So far, the rebalancing effort has had both stabilizing and destabilizing effects. On one hand, the UN has managed to maintain operational continuity and uphold its legitimacy in key policy areas such as global health responses, climate change action, and humanitarian aid despite Trump-era volatility. On the other, the rise of new donor-influencers, especially China, raises questions about normative coherence within the organization. Increased influence by non-democratic states could gradually reshape the UN’s agenda, particularly in areas such as internet governance, development finance, and human rights monitoring. The key question remains whether this shift will strengthen the UN by making it more inclusive and multipolar, or whether China will leverage its position primarily for its own geopolitical and economic gain. Still, Guterres and allied leadership figures have framed these challenges necessary in the face of evolution toward a more inclusive and flexible multilateral order. In an international system where the U.S. increasingly leans toward isolationism and unilateral action, the UN’s survival as a legitimate institution relies on its ability to reimagine global cooperation through diversified funding streams, collective leadership from nontraditional actors, and coalition-based diplomacy.

WHO, WTO & Policy Adjustment

The WHO and the WTO have also faced major structural dilemmas. Throughout his presidencies, Trump has frequently accused both organizations of being biased against U.S. interests and undermining American sovereignty. His decision to withdraw from the WHO on his second day in office, initiated during his first term amid a global pandemic, marked an unprecedented moment in U.S. global health diplomacy. The stated rationale was the WHO’s alleged pro-China bias during the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, but the decision ultimately reflects a broader disdain for institutional constraints on U.S. policy freedom. Although President Biden reversed the initial withdrawal, the incident destabilized the WHO’s credibility and necessitated internal reform efforts. Director-General Tedros Adhanon Ghebreyesus responded by launching a new program ‘Pandemic Hub’ for outbreak surveillance and early warning, which empowered more regional and non-state actors and diluted WHO reliance on any one national donor (Sanchez). Based in Berlin, this WHO Hub represents a geographic and institutional pivot toward EU cooperation and away from U.S. centrality. Ghebreyesus also launched initiatives to expand assessed contributions, including new mandatory fees to be paid by member states. He built stronger partnerships with non-traditional funders, such as private foundations including the Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust, and increased engagement with regional health authorities to create a more resilient network of actors in global health governance. These adaptations, though not brand new, gained urgency after the Trump-era shock and demonstrate broader survival strategies. Though far from insulated from geopolitics, the WHO’s post-2020 moves represent a reorientation toward multilateralism without overreliance on any single state actor.

The WTO, meanwhile, is experiencing a larger crisis. Trump has continuously challenged the foundations of the international trade system, launched trade wars, imposed unprecedented tariffs on traditional allies such as Canada and the EU, and criticized the WTO as “broken” and “unfair” to the US. His administration systematically blocked the appointment of judges to the WTO Appellate Body, rendering the dispute settlement system inoperable by December 2019. This effectively disabled the WTO’s ability to enforce trade rules, undercutting one of the core mechanisms of global economic governance. In response, member states began forming alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. Most significantly, the EU, Canada, and several others established the Multi-Party Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) in 2020, a workaround that replicated the functions of the WTO Appellate Body but excluded the US. This shift towards ‘minilateral’ cooperation within a multilateral framework could allow like minded states to uphold rule-based international trade despite American disengagement.

At the same time, WTO Director-General Ngozi Okojo Iweala, appointed in 2021, identified institutional reform as a top priority. Under her leadership, the WTO began reassessing rules on industrial subsidies, agriculture, digital trade, and climate-related commerce to maintain relevance in a shifting geopolitical and economic context. Both the WHO and WTO cases reveal a clear pattern: U.S. retreat has not led to institutional collapse but instead sparked adaptations in governance structure, funding models, and strategic alignment. These organizations embraced a more distributed structure of authority and legitimacy, moving toward ‘post-hegemonic multilateralism’, meaning that rather than relying primarily on one dominant global power to lead and fund them, international institutions are shifting toward shared leadership and decision-making among multiple countries. This approach helps make these organizations more resilient and adaptable, especially when the actions of a single powerful country become unpredictable. While the United States remains the most powerful actor in the international system, its actions under Trump highlights the dangers of over-concentration and the strategic imperative of diversification. As the WHO began building health security capacity through regional hubs and digital innovation partnerships, the WTO experimented with plurilateral agreements and institutional modernization. In both cases, the threat of a dangerous and unilateral U.S. decision forced a recalibration of diplomatic expectations and an increased reliance on coalitions of middle powers to uphold global norms. The WHO and WTO’s survival strategies were neither purely reactive nor fully premeditated, but instead reflect a growing awareness that 21st-century multilateralism requires agility and resilience in the face of great power volatility. While the long-term consequences of this evolution remain to be seen, what is clear is that international institutions can no longer assume consistent U.S. stewardship.

Implications for Global Governance

The Trump administration’s repeated antagonism toward multilateral institutions has done more than just disrupt diplomatic norms — it has kickstarted significant realignment in global governance. By undermining traditional alliances and threatening withdrawal from respected institutions, Trump’s foreign policy has created both power vacuums and a crisis of legitimacy within the liberal international order. As the U.S. appears increasingly reluctant to bear the costs of global leadership, states such as China and Russia seize the opportunity to expand their influence. By investing in forums such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, both rising powers have signaled an effort to build parallel governance structures that challenge the Western-led status quo. The most tangible sign of this shift has been the growing prominence of BRICS, a loose coalition of emerging powers including Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa that recently expanded to include Saudi Arabia and Iran. While the bloc has yet to coalesce into a unified counterweight to the G7, its recent push for de-dollarization and alternative payment systems demonstrates the desire among many global south states for a more multipolar economic order. However, despite rising calls to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar, American monetary hegemony remains deeply entrenched. As of 2024, the dollar still accounts for nearly 60% of global foreign exchange reserves and over 80% of international trade invoicing. This is due not only to the size and relative stability of the U.S. economy but also to the depth of American financial markets and the lack of credible alternatives. The US’s continued dominance in global monetary stability, anchored by the dollar’s central role in international finance, and the widespread reliance of other countries on American debt through Treasury securities give Washington significant leverage. This financial entrenchment allows the U.S. to exert outsized influence over international institutions and global economic norms. Trump’s willingness to challenge allies and partners reflects a belief that, despite diplomatic friction, the U.S. holds the strongest cards due to its unique position as the issuer of the world’s primary reserve currency and the indispensable provider of global liquidity. In other words, the U.S. can afford to adopt a tougher stance because many countries depend on access to U.S. markets, capital, and financial infrastructure, maintaining American primacy even amid political upheaval. Nevertheless, a Trump-era of foreign policy reveals the critical truth that institutional legitimacy is not guaranteed, even as material dominance persists. While the U.S. may retain its centrality in global finance, its political authority within multilateral institutions grows more contested. The erosion of trust and prevalence of unpredictability over Trump years has left even close allies hedging their bets, investing in regional forums, alternative coalitions, and more distributed defense structures.

Conclusion

The post-Cold War era of uncontested American hegemony is giving way to an uncertain, multipolar world order. Amidst this shift, the role and resilience of international organizations have come under increasing scrutiny. As examined through the cases of NATO, the UN, the WHO, and the WTO, U.S. foreign policy, specifically under Trump administrations, has often prioritized unilateralism, transactional moves, and national self-interest over longstanding commitments to multilateralism. These shifts have significantly altered the financial, political, and normative foundations of the international institutions that have historically relied on U.S. leadership. Yet rather than collapsing under pressure, these IOs have largely adapted. NATO has diversified its strategic focus and defense responsibilities, redistributing leadership and rethinking military readiness for a new era of hybrid threats. The UN has sought to broaden its financial base and leadership representation, buffering against the volatility of U.S. support. Similar efforts in the WHO and WTO illustrate how institutions are learning to recalibrate priorities, build new alliances, and become more self-reliant. Widespread institutional resilience suggests that while U.S. influence remains a critical factor, it is no longer the sole guarantor of international cooperation. The future of global governance will depend on how well IOs can continue adapting to a world where power is more diffuse, threats are more complex, and leadership is less predictable. Constructivism offers hope that norms of collaboration, mutual responsibility, and institutional legitimacy can evolve beyond dependence on a single hegemon. In an age of rising nationalism and strategic competition, the survival and effectiveness of international organizations will rely not only on their capacity to innovate, but on the willingness of global actors to invest in a shared international order.

Leave a comment