Kathryn Stevens, The University of California – Santa Barbara

Abstract

In this paper, I will explore the historical basis for the classification of terrorist organizations and how this labeling has impacted U.S. foreign policy and communities in the Middle East. I will analyze the ongoing definition of terrorism, how it has evolved, and how it impacts the Middle East today.

The evolving development of – and often politically charged – definitions of terrorism have significantly impacted communities in the Middle East by shaping international policies and justifying military interventions. Ultimately, this has affected social cohesion, economic stability, and perceptions of deserved justice in the region. In exploring the roots and changing definitions of terrorism, this article unpacks who is considered a terrorist and why. The analysis focuses on explaining the double standard of state-sanctioned violence when compared to organizational violence with political goals, and exposing the contradictions that nation-states uphold in their use of violence to counteract violence. I also aim to classify their violence and explain how it is different, if it is, from terrorism.

Keywords: Terrorism, Foreign Terrorist Organization, Definition, Violence, Middle East

I. Introduction

The dominant cultural definition of terrorism – as irrational, unprovoked violence detached from state legitimacy – has played a central role in the dehumanization of the Middle East and its people, and has stemmed from policy made in the US. By framing acts of resistance or conflict as “terrorism” only when they are not tied to recognized states, Western discourse implicitly denies Middle Eastern communities the right to self-defense or political agency. This narrative constructs these populations as inherently violent and thus undeserving of international protection and justice. At the same time, it conveniently obscures the responsibility of nation-states, particularly Western powers, whose imperialist interventions have destabilized the region. These powers dismantled functioning governance structures and left behind states dependent on insufficient international aid. In doing so, they not only avoid accountability for long-term consequences but also create a justification for re-engagement in the region under the guise of combating terrorism. A historical examination of the definitions of terrorism in U.S. policies and the events they followed can help us understand how these narratives were constructed and weaponized to serve geopolitical interests. This cycle perpetuates interventionism and reinforces global power imbalances, all while erasing the legitimacy of local struggles for sovereignty and dignity.

II. Foundational Definitions

Policy definitions of terrorism were founded primarily after terror events in the 1980s in the United States and around the globe. During that decade, the U.S. was facing increased domestic terrorism and also bearing witness to the rise of foreign extremist violence. At home, domestic terrorist events were occurring at higher frequencies, organized by diverse factions like pro-independence Puerto Rican groups, leftist radical groups, far-right extremist groups, and Jewish extremist groups. They ranged from high-profile robberies to bombings, assassinations, and kidnappings. These attacks demonstrated to law enforcement that radical movements like the Black Panther Party and white leftist terrorist organizations that had emerged in the 60s and 70s were still very active. It also indicated that new threats were emerging on the home front that challenged the validity of United States nationhood, like the Puerto Rican independence organizations. Domestic terrorism emerged as a perceived threat to the U.S. government largely because many of the groups challenged the system that breathed life into America— capitalism. In an FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin published in October of 1987 discussing terrorism, the Intelligence Research Specialist in the Terrorist Research and Analytical Center attributed the roots of radical left bases to Marxist, Leninist, and Maoist teachings, opining that “They [domestic terrorist groups] perceive that many ills exist in the United States, both socially and politically, which they blame on the U.S. Government. They also view the Government as being capitalistic, militaristic, and imperialistic.” The FBI noted the proposed solution suggested by leftist radicals was to destroy the root cause of these problems, the capitalist system, by any means possible. While some domestic terrorist groups challenged the U.S. political and economic order from within, others were motivated by international conflicts and sought to influence, or retaliate against, America’s foreign policy positions. For instance, Jewish extremist groups were linked to approximately 20 domestic terrorist incidents in the 1980s, a majority of which were against people or organizations that were considered anti-Semitic or too supportive of Arab efforts against the interests of Israel. Other groups were motivated by racial hate. White supremacist bombings, murders, and arson rose in the 1980s as the Aryan Nation and its offshoots became significant. White leftist terrorism saw a rise in the 1980s too, responsible since 1981 for 21 domestic bombings or attempted bombings. The higher frequency and overall culmination of these domestic events triggered the FBI to move terrorism to its 4th highest priority and start to focus attention, money, and resources on it. The FBI concluded this 1980s bulletin on terrorism by determining it as “cyclical in nature”, rightfully acknowledging the perpetual character of violence.

In the 1987 bulletin, terrorism was defined as “the unlawful use of force or violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” This definition would undoubtedly influence the emerging definitions of foreign terrorism in domestic and international policy. This framing positions terrorism as the pursuit of some ideological, religious, or personal belief through offensive action against the state rather than a defensive action as a response to systematic oppression or territorial sovereignty. The government responded to this definition by creating special task force teams, training its operatives in the theory and politics of terrorism, and by exploring the origins of terrorism and tracing its development back from early stages to a modern mode of conflict. This definition would be foundational in the early framework of defining and classifying foreign terrorist organizations as engaging in irrational, unprovoked violence, stripped of any claim to self-defense because they are not tied to a state. As this definition was applied to Foreign Terrorist Organizations, it dehumanized the Middle East, the communities and people that live there, making them unworthy of protection and justice. It removed responsibility and accountability from nation-states whose imperialistic endeavors left the Middle East stripped of effective government structure and reliant on lackluster funding from the international community, which allowed them to justify their re-entry into the Middle East through the guise of destroying terrorism.

Towards the end of the 1980s and during the 1990s, the U.S. government began to look outward to foreign terrorist threats following an increase in general conflict that wasn’t associated with state governments, but paramilitary groups. The U.S. was particularly interested in the Middle East, having historical policy ties to Israel, and supporting Iraq in its war against Iran in the 80s. In 1986, the Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act was signed and passed by Ronald Reagan in an effort to expand the U.S. foreign ability to secure embassies and consulates, and assist foreign governments in combating terrorism. In tandem with other efforts to curb and identify rising terrorism activity in the US, it was written and passed to stop suspected terrorist groups from raising funds in the U.S. Then, in 1987, the Anti-Terrorism Act was passed, which singled out the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a terrorist organization following the murder of a U.S. citizen overseas. The PLO at the time was the only representative party for Palestinians, who weren’t allowed formal governmental institutions under the British mandate. This made the creation of civic organizations extremely difficult in Palestine, leaving Palestinian interests with little to no representation. PLO was thus designated as a terrorist organization in this law before Foreign Terrorist Organizations were legally constructed in the US. However, when the list of FTOs was published in 1997, the PLO was ironically not on the list. This inconsistency highlights how the U.S. government’s application of the “terrorist” label has been shaped more by shifting political alliances than by consistent legal or moral criteria.

The 1987 terrorism definition in the FBI bulletin was reiterated in policies that would legally classify terrorism, like the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of Fiscal Years 1988 and 1989. Here, a terrorist attack is defined as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.” The groups that take this action must also “retain the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity or terrorism.” The third criterion determines that the organization’s “terrorist activity or terrorism must threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national security (national defense, foreign relations, or the economic interests) of the United States.” This reveals the fundamentally self-interested nature of the legal framework: violence is only classified as terrorism if it threatens U.S. nationals or national interests, suggesting that acts of political violence are not inherently illegitimate, but become so when they challenge or oppose American power.

Ten years later, the U.S. Immigrant and Nationality Act amended in 1996 listed terrorist activities as “any activity which is unlawful under the laws of the place where it is committed (or which, if committed in the United States, would be unlawful under the laws of the United States or any State)” and which involves actions like hijacking vehicles, threatening to kill individuals to compel a third person, attacking an internationally protected person, assassination, use of biological or chemical agents, using firearms, or threats to do any of the above. A foreign terrorist organization is thereby designated by the Secretary of State if it is, 1) a foreign organization, and 2) has perpetrated one or more of these activities, and 3) the said activity threatens the security of the U.S. or U.S. nationals.

III. International Implications

This sweeping definition reveals its intent to group a vast and varied set of actions under the same label, and simultaneously targets specific actors. For instance, “subnational groups or clandestine agents” can only be applied to stateless people, extremists not tied to a state, and political organizations. When violence occurs that is executed on their behalf, terrorism is an applicable label. This means no nation-state actor can be considered a terrorist organization under any of these criteria. Simultaneously, state violence cannot be considered terrorism, as recognized statehood protects its violence from the label of ‘terrorism’. The same protections, if civilian death is unintended, do not apply to stateless groups. This framework denies stateless groups the benefit of the doubt, presuming malicious intent and cruelty, while stripping them of any claim to territorial self-defense. At the same time, it absolves Western powers of accountability for their own histories of imperialism and state-sanctioned violence. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the mandate system imposed by Britain and France forced Middle Eastern communities to submit to foreign rule that neither reflected nor prioritized their political or cultural interests. This led to the creation of a significant number of organizations who would later be classified as FTOs, as they advocated for the rights and freedoms of their communities and defended their territory against invasion, namely Hezbollah and the PLO. Secondly, the definition of national security means “the national defense, foreign relations, or economic interests of the United States.” The use of “or” instead of “and” here broadens the scope of this law, and could allow for attacks primarily against economic interests that do not cause casualties or wounds to be argued as terrorism. It also means that attacks against foreign allies’ economic interests, if tied to the U.S., would be constituted as terrorism if they fulfilled the other criteria.

The intended effects of designating groups as terrorist organizations by the FBI are listed as: curbing terrorism financing, stigmatizing and isolating terrorist organizations, heightening public awareness of terrorist organizations, and signaling concern of named organizations to other governments. This framing designates all anti-terrorist efforts as crucial and noble, mobilizing and convincing a relatively uninformed American civilian population of their urgency. The special attention and unique designation that these groups receive with the label “terrorist organization” represent them as groups that only function to execute violence, so egregiously dangerous that they need to be destroyed and isolated at any cost to the American Taxpayer. The list of intended effects conveniently ignores that the policy framing grants the U.S. broad legal and moral authority to criminalize political organizations that challenge global economic structures, including those seeking national liberation, sovereignty, or self-determination. For these groups, especially if stateless or operating within disputed territories, the label of “terrorist” effectively delegitimizes their political aims and opens the door to foreign intervention. It also pressures the countries in which these groups are based, often already fragile or postcolonial states, to align with U.S. interests under threat of economic or diplomatic consequences. Meanwhile, the civilian populations are made vulnerable to surveillance, displacement, or even targeted violence – all justified through the expansive and politicized use of the terrorism label.

IV. The Beginning of the War on Terror

Without international backing, on October 7, 1997, 13 organizations were added to the U.S. list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). This was in response to their increased violent activity, namely Hezbollah, National Liberation Army, and the Palestine Liberation Front, in armed combat against Israel in the Middle East. Following these designations, in 1998, two sister bombings in Kenya and Tanzania took place at American embassies, killing 224 and wounding over 4,000. Al-Qaeda under Osama bin Laden, who in the following decade would become the face of terrorism worldwide, took responsibility for ordering the attacks. Sources that were close to him at the time explained that his reasoning behind the attacks was in defiance of the American troops’ presence in Saudi Arabia. The attacks had taken place eight years to the day after American troops were ordered to and arrived in Saudi Arabia. Before the attacks, bin Laden issued a warning fatwa, or a religious declaration, called “Jihad against Jews and Crusaders.” In this, he warned that it was his prerogative “To kill Americans and their allies, both civil and military, is an individual duty of every Muslim who is able, in any country where this is possible,” until American armies, “shattered and broken-winged, depart from all the lands of Islam.” U.S. military involvement in the Middle East during the late 80s and 90s had evidently stirred the anger and distrust of Western governments, by demonstrating their new age imperialist goals, and moving people to a point of extremism and terror. The interventionist policies the U.S. government had engaged in inside the Middle East, like the first Gulf War, the stationing of troops in Saudi Arabia, and the classification of Palestine Liberation groups as FTOs, completely backfired. They catalyzed anti-Western terrorism, which in turn spurred the creation of the FBI counterterrorism task force.

The bombings in Kenya and Tanzania also garnered incredible, widespread international attention and efforts focused on identifying, condemning, and ending terrorism. U.N. resolution 1269 of October 1999 was the first articulation of this. The resolution first acknowledged that terrorist acts were increasing and condemned them on an international stage. They then moved on to list a set of goals for the general assembly to resolve, the most notable of which stated that all signatories; “Unequivocally condemns all acts, methods and practices of terrorism as criminal and unjustifiable, regardless of their motivation, in all their forms and manifestations, wherever and by whomever committed, in particular those which could threaten international peace and security.” Important to note here is the language “regardless of motivation.” This articulates the same power dynamic of the U.S. Foreign Relations Authorization Act because it strips stateless people of the right to self-defense. It demonstrates how U.S. hegemonic power in international spaces like the United Nations protruded in international policies and designations logic.The language itself continues to dismiss provocations by nation-states upon their imperial assets and relieves them of accountability in the actions of terrorist groups. Imperialist powers have an important tie and relation that they cannot deny if they continue to spew anti-terrorism policy domestically and internationally. On the other hand, it is also important to acknowledge that condemning these acts was necessary. The targeted use of violence by any group, state-led or not, is immoral, but the United Nations and the United States provided a legal framework that swept away legacies that colonial and imperial powers left. This allowed groups with no formal government to be punished internationally for violent actions intended to serve as self-defense, equating their violence with violence executed for the sake of malice.

These policies were constructed and passed so that, following the September 11th attacks, the U.S. was prepared to swiftly take action to launch the War on Terror. 9/11 was a brutal demonstration of the lengths people would go to prove political points by claiming the lives of 2,977 people. It shook confidence in national security and exposed the vulnerability of even the most modern, western, and ‘developed’ states. The shock of the attacks evoked strong policy and administrative reactions from the White House, Congress, and international actors, which would truly begin a War on Terror with no definitive end.

First was Executive Order 13224 on September 23, 2001, which was made to target the financing of terrorist organizations that were classified under the criteria described earlier. This had more impacts than just the targeting of al-Qaeda. It led to the Lebanese Canadian Bank being shut down in 2011 after being designated for laundering drug money for Hezbollah. It shut down charities like Al-Haramain Islamic Foundation, which forced Saudi Arabia to restructure its charity sector and tighten oversight. The Executive Order was also used to target the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), especially the Quds Force, limiting Iran’s ability to support its proxies across the region. This was followed by UN Resolution 1368 on October 19th, which reiterated the outlines for anti-terrorism policies in Resolution 1269 of 1999. Then came the U.S. Patriot Act on October 26, which strengthened U.S. measures to prevent, detect, and prosecute international financing of terrorism. Passed by Congress, it was a representation of the general population’s justified anxiety over terrorism, and a movement towards the prioritization of the developing War on Terror. All of these actions targeted groups in the Middle East, contributing to the already established notion that they were nations that harboured terrorists. This pulled money away from those nations, deeming them as unworthy recipients of international funds because they were constructed as the birthplace and safehouse of terrorist activity. In pulling money away from banks and organizations that weren’t tied to the state, the U.S. demonized their work even if it wasn’t related explicitly to terrorist activity. This financial isolation further entrenched underdevelopment, instability, and resentment. By further exacerbating economic instability, these policies limit the ability of civilians to resist authoritarian governance or the rise of militant actors. This vacuum of power and stability serves as justification for U.S. and Western intervention strategies, yet many of these regimes and crises emerged in the first place as a direct consequence of previous Western involvement. In this way, policies aimed at countering terrorism have not only reinforced the cycle of marginalization and violence but also reproduced the very conditions that give rise to extremist power.

V. Contradictions of Classifying Violence

A large part of the impact of classifying terrorism corresponds to the perceived deserved justice of communities, or the moral entitlement of their people. Palestine’s exclusion from the UN, as the U.S. continuously blocks its entry, exemplifies this disparity. Because of its lack of recognition as a state (46 U.N. member states don’t recognize it, 147 do), Palestine has no ability to formally advocate for itself on an international stage. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which formally renounced the use of terrorism in 1988 and committed itself to peace with Israel in several agreements since the 1993 Oslo Accords, still faces extreme setbacks. This is in part due to the biases it has faced since the 1980s, constructed through the 1987 Anti-Terrorist Act. That law was motivated by the killing of a U.S. citizen abroad, which contributed to the double standard for violence of state actors and stateless actors. For instance, documents declassified in 2004 show how in the 6 Day War of 1967, Israeli troops attacked USS Liberty, killing 34 and wounding 170. However, this violence was never classified as terrorism, despite the casualties it caused. When stateless people commit violence, it is rarely given the benefit of the doubt while states are often given more leniency. The 1996 Israeli military campaign known as Operation Grapes of Wrath further highlights these contradictions. The Israeli operation devastated Lebanese infrastructure and killed over 150 civilians. This attack was never considered terrorism. During the conflict, Hezbollah, which would become a designated FTO in 1997, provided medical assistance to everyday citizens. Their Islamic Health Committee (IHC) mobilized 72 ambulances and 217 medics, helping to get civilians out of direct fire, yet another example of the contractions that the label terrorist glosses over. Humanitarian actions are often ignored under the blanket label of “terrorism,” which erases nuance and flattens the moral complexity of an organization.

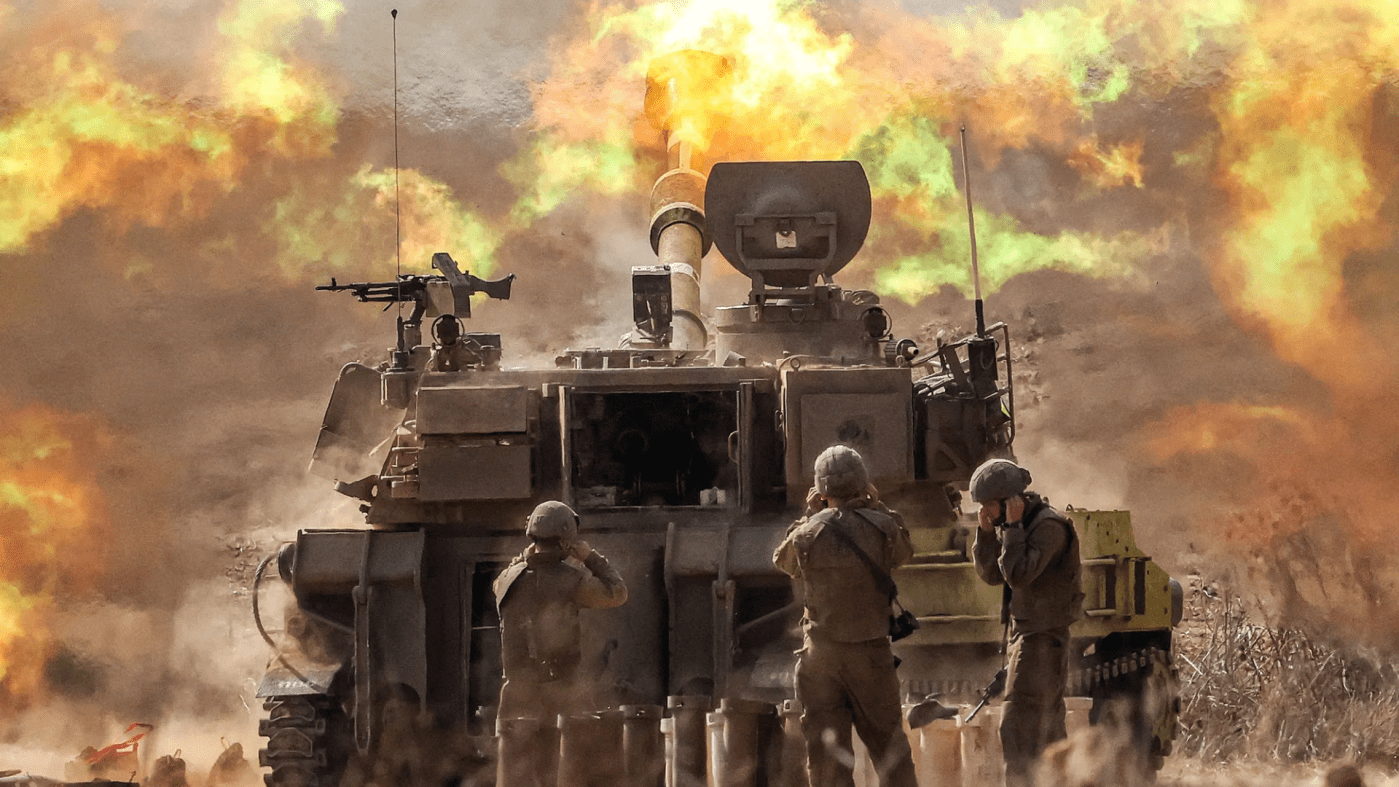

American violence, too, has escaped the terrorism label, despite its devastating civilian toll. A study by Brown University found that between 408,749 and 432,039 civilians were killed directly by violence in post 9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Other Post-9/11 War Zones. Another study concluded that at least 22,679 civilians were directly killed by U.S. strikes since 9/11, with that number potentially as high as 48,308. Reactionary violence carried out under the thin veil of the War on Terror proved to be just as violent, if not more, than the violence that it claimed to oppose. It perpetuates the cyclical nature of terrorism while simultaneously avoiding consequential criticism because it isn’t classified as illegitimate violence, despite its civilian toll. This discrepancy skews global perceptions of justice, silencing those who are denied the right to even articulate their suffering on the world stage.

VI. Conclusion

Evidently, the U.S. is involved in taking lives in efforts to expand, protect, or promote its own political goals. I encourage you, as the reader, to measure this against U.S. policy definitions of terrorism through some seeds for reflection. What kind of violence, if any, is justifiable? Who makes these rules? Who has power in these situations, and how does that affect their outcomes? How are contradictions and justifications for violence inherent to the “cyclical nature” that the FBI prescribes terrorism? Should there be empathy in terrorists’ actions by understanding the multi-generational impact of imperialism? Or should we continue to avoid and neglect the obvious impact that these had on the Middle East? Should understanding where violence is rooted be mutually exclusive from endorsing it? Or can you understand it, condemn it, and make policy changes that acknowledge the contribution to the roots of violence? These are the questions we need to ask to change the way we think of terrorism.

Framing terrorism in stark black-and-white terms oversimplifies deeply complex histories and relationships. U.S. policy reveals a clear double standard in how violence is classified. When the U.S. and other imperial powers begin to take accountability for their roles in creating hostile environments in the Middle East, real change becomes possible. Continuing to respond to violence with more violence perpetuates a cycle of interventionism, reinforces global power imbalances, and delegitimizes local struggles for sovereignty and dignity. To honor the lives and memories of victims of terrorism, we must examine the root causes that provoke such violence. This demands a radical rethinking of the policies we accept and the narratives we uphold. Understanding where violence is rooted does not require endorsing it. We can condemn acts of terror while also recognizing the historical conditions and systemic injustices that contribute to their emergence. Only by confronting these contradictions can we move toward meaningful, nonviolent solutions. Breaking this cycle means reimagining security—not through domination, but through justice, accountability, and empathy.

Leave a comment